.jpeg)

“What happens when an object is no longer functional?” How do you see your works answering this particular question?

In general, my creative practice is grounded in an inquiry into how new technologies throughout history have altered the production, perception, and preservation of culture. My work in the group show, Bespoke Matter deals specifically with aged analog film and the shifts in color value that naturally occurs when film begins to decay with time and exposure to elements. One could say decaying film is no longer functional as it has lost the capacity of accurately representing a photographic representation of a moment in time, however, by using new technologies to scan, analyze and reconfigure the source material, a new function emerges. Rather than representational documentation, the images serve as proof of the change of materiality over time.

I have also been thinking about how aging technologies reflect a wider cultural value system around decline and care. Dirk van de Leemput writes that as a technology becomes obsolete, artists and cultural institutions that support artists, are often the final acts of resistance. Rather than rush to replace older technologies, artists, museums, galleries, and media arts centers, take extreme measures to preserve antiquated tech. Perhaps this is because “function” and “efficiency” are not the cornerstone of art making, rather, expression and reflection of wider cultural concerns are. Working with non-functional objects and antiquated processes adds to the meaning of the creative production.

.jpg)

Your work in Bespoke Matter is exhibited alongside artists who specialize in different materialities such as steel furniture, clay, and paper. How does your work engage and differ with decorative arts traditions?

Chromatographic Landscapes includes a series of thirteen illuminated art panels wired with cloth covered color cords displaying images printed on silicone edge fabric. Lighting design has long been used as a crucial component in decorative art traditions. Additionally, Chromatographic Landscapes includes four digital Jacquard loom woven tapestries. These weavings are both a reflection of traditional decorative arts as well as the history of computer technology as the Jacquard loom was the historic precursor to Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, a machine considered to be an early mechanical computer. The Jacquard loom used punched cards to automatically weave complex patterns and Babbage adapted this concept to use cards for a series of calculations. Tapestries have a rich history in decorative arts. With Jacquard’s card system, it was possible to weave intricate images that weren’t necessarily constrained by repeatable pattern.

.jpg)

You discovered Ben Kabakow’s photographs from your friend who inherited her friend’s family slide collection, Deb Rudman. Ben Kabakow was her grandfather who was a NYC postal worker and photographer. You mention that your work surrounds using domestic archives as source material. Is there any interest to you personally about taking these otherwise private sources and bringing them to light and public view?

Part of my appreciation of the Ben Kabakow’s slide collection is the care and dedication he and his family took in preserving the images. My own families domestic archive, or at least what I know of it, is rather slim. On my paternal side, I have a few faded images of my father’s family in Eastern Germany before they immigrated to the United States in 1953. On my maternal side, there are a few printed photographs but they are scattered in boxes with very few notes. Ben Kabakow’s collection of slides is intricately documented and is not just of family, but places he traveled. Deb shared that it was a tradition in her family to gather at her grandfathers’ house and for slideshows that he would curate for different occasions. And this is how I was introduced to the slide collection, Deb invited my husband and I over to her house for a slide show of images taken by her grandfather of Italy. This intentional preservation and sharing of personal history is unique and worthy of amplification.

For your exhibition at Old City Publishing, you hand crafted six illuminated art panels using visuals inspired by Ben Kabakow. What drew you to Ben Kabakow’s photographic 35mm slides and his urban language as inspiration for Reimagined Street Scenes?

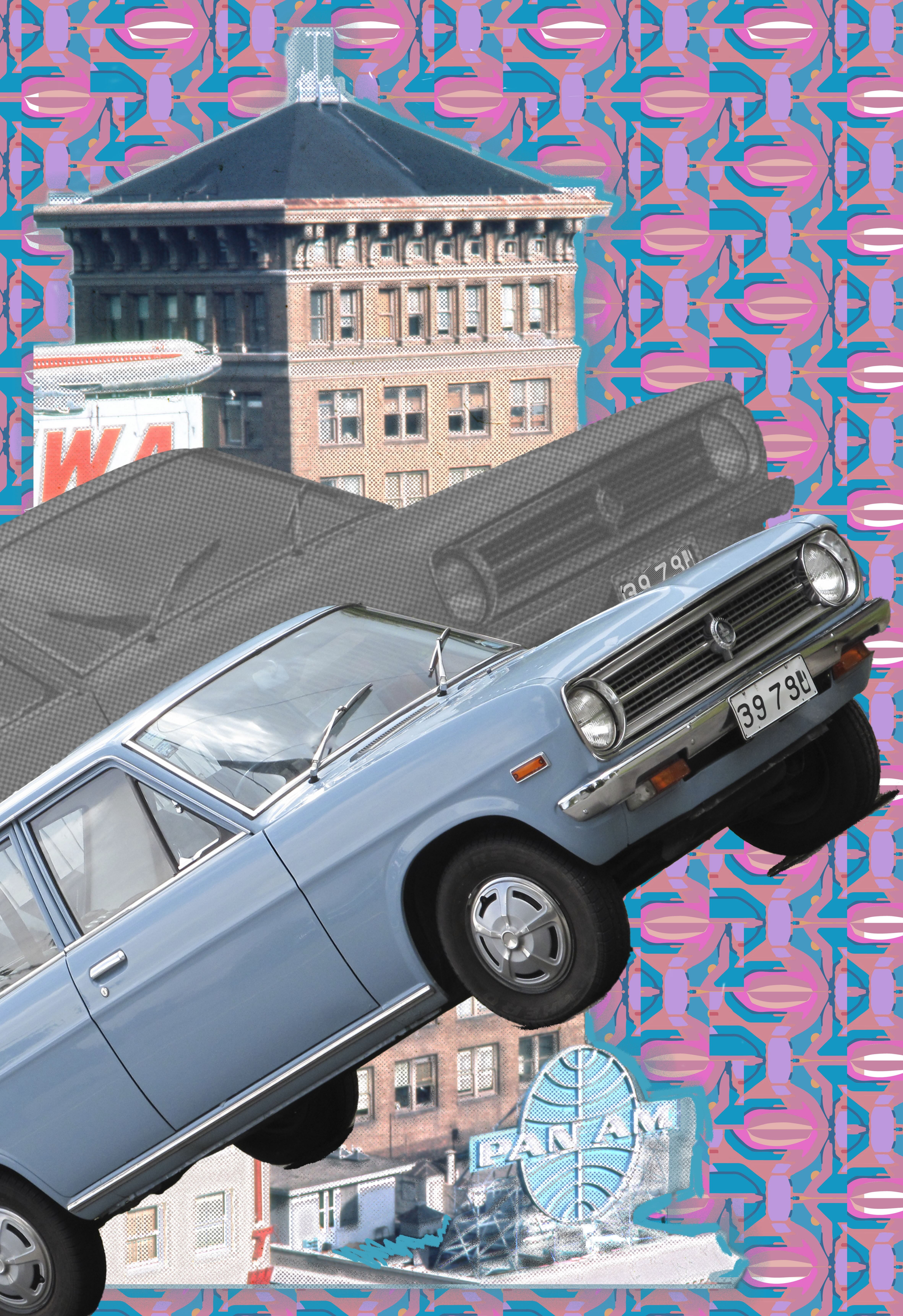

I had been analyzing Kabakow’s slide archives as a whole, treating the collection as a vast visual data set. Given the opportunity to design new work for Old City Publishing, I decided to see how I could use the same source material in a completely different way. After studying the slides for nearly two years, I was very familiar with the content. I had organized the digital scans by location and then subject matter. For example, the folder structure Rome > Cars contained numerous scans of slides from the archive that were shot in Rome and had cars as a central feature. Considering the location of Old City Publishing and the likely audience of urban pedestrians and passengers in cars, I wanted to celebrate the urban experience and highlight the iconic architectural, transportation, and street experience of various cities around the world in the mid-1900’s as seen by Ben. Extracting nostalgic and recognizable elements from the original images allowed additional compositional decisions and elements.

Storefront exhibitions like the one at Old City Publishing are visible 24/7 from the outside. Does the constant visibility to passerbys affect your creative decisions differently than gallery installations?

Knowing the work would be visible by people walking and driving by the storefront impacted my formal design decisions. I intentionally increased the size of objects and used bright, distinguishing colors to visually separate key subject matter within the images. Placing less importance on small details, my objective was to provide visuals that could be easily comprehended and enjoyed.

You began interacting with analog and digital processes in the early 2000’s when digital video technology was still emerging. How has your relationship with technology evolved as digital infrastructure has become increasingly advanced?

In general, my creative process is tech forward and embraces the use of emerging media. The core conceptual concerns, however, are not limited to digital tech but rather on the trajectory of historic developments with technological innovations that have happened prior to today. Because of this, I use a wide range of technical processes, both analog and digital.

I will say, however, that in the early 2000’s, when I first had the opportunity to work with digital video and basic web coding, digital tools were very accessible and easy to learn. As digital infrastructure has become increasingly advanced with more layers of complex code and specialized devices, it has become more challenging to afford and subvert the established technical systems for creative purposes. By 2013, when I graduated with my MFA in Film and Media Arts, I found myself spending more time attempting to learn new technologies than actually making work. This is partly what attracted me to working with analog material including 35mm slides. By starting with source material that is physical rather than digital, the latitude for my artistic mark is greater.

You describe your practice as celebrating memory and history. In an age of instant documentation and digital innovation, what role do you see for artworks that engage with historical imagery?

It is a complicated time to be creating digital art utilizing history imagery. With recent advances in AI, a heightened concern around deep fakes, and the push to return to hand-made practices within the arts, it feels a bit risky to engage with images that have been transcoded from an analog substrate into digital pixels. I’ve never intended my work to serve as representational documentation or news reporting, and therefore, should not held to the same standards of “truth” as say a documentary film or news reels, however, I do feel it is important to be transparent about the tools and processes I use in treating the images.

You created an algorithmically generated wallpaper in collaboration with Andrew Hart and the Jefferson University’s College of Architecture and Built Environment. How did you approach translating architectural and technological data into a decorative surface pattern and what does wallpaper, as a medium, allow you to explore that other forms of art lack?

This project was a site-specific installation for “Philadelphia Forthcoming: The Endless Urban Portrait” curated by the Da Vinci Art Alliance in South Philadelphia. The theme of the show was Philadelphia’s architectural past and its potential future. Da Vinci Art Alliance is located in an old S Philly row home has many remarkable architectural features. In researching the history of industry and Philadelphia, I discovered the city was once known as a hotbed for wall paper manufacturing. Given the trajectory of how wall paper was originally produced using large hand pressed blocks to today’s fully digitized printing methods, I thought it a good medium for exploring the past and future of tech in Philadelphia.

One of the benefits of starting with wallpaper as a source material is many of the pattern books have been digitized and placed in the public domain. Also, wallpaper is intended to be repeated over large areas, making a perfect study for installation work that needs to fill space. Working with a set of 600 jpegs sourced from wallpaper sample books, I created a series of digital data sets. I then trained an algorithm on the old wallpaper designs to see what new patterns the algorithm could generate. The result was an infinite number of unique images that retain certain qualities that reflect patterns and qualities of the original sample but aren’t traceable to any one specific image.

Working with Andrew Hart and the print shop at Jefferson University, patterns created from 6-8 computer generated images were printed on fabric. This iterative process is a metaphor for how design practices are transformed through the introduction of new technology.

Since founding Lisa Marie Patzer Studio in 2022, you’ve worked with private clients, interior designers, and business owners to create site-specific work for bespoke commercial settings and private residences. Can you expand upon the process of creating site-specific work, and what does the collaborative process look like when working with clients?

When creating work for clients, I take a highly collaborative and iterative approach. Ideally, the timeline will allow for a series of conversations with the client about their unique space and how my visual work can help satisfy a need. Often clients are looking for a unique work of art that will integrate storytelling and design. I am open to working with source materials provided by the client as a basis of the work.

For example, in 2024 I was commissioned by a family to create a statement piece for the entryway of their home. They wanted the art to evoke conversation with their daughter about this history of their family as well as the location of their home that was situated on North Table Mountain in Golden, Colorado. Specific motifs emerged from a series of conversations and I utilized photos provided to me by the family as well as historic images of the region to create abstract, story-driven, illuminated images.

Your artist statement describes your process as involving “deep listening to place.”. Can you describe what that listening looks like in practice? What are you listening for and how does a place communicate its stories to you?

When doing site-specific work, I find it helpful to familiarize myself with the space. Both in terms of architectural features as well as how a space is activated. Ideally, I will have time to research and ask questions regarding how a place has changed over time, who were the original inhabitants, how did commerce and environmental factors influence the infrastructure. From this research, I often discover remnants of the past that can be brought into conversation with and influence whatever design I’m working on.

Bespoke Matter is on view at Park Towne Place through January 20, 2026. You can learn more here and shop the exhibition here.